Redistribution Or Recognition?

A conversation between Thomas Piketty and Michael Sandel offers an occasion to revisit the debate.

On January 18, the New York Times ran an opinion piece in the form of a brief exchange between the philosopher Michael Sandel and the economist Thomas Piketty on the state of post-Biden America. In summing up the piece in the introductory text, the editors write that the two thinkers’ “back-and-forth [...] builds to a surprising conclusion: that the left must reclaim a form of identity politics.”

It’s tough to imagine a more perverse reading of the exchange. The final line of the article, offered by the socialist Piketty, essentially suggests the exact opposite: “if your socioeconomic aspirations are neglected too long and too obviously,” he writes, “then at the end this can give rise to entrenched identity conflict.” What is required of the Left, Piketty clearly suggests here and throughout the rest of the article, is a renewed commitment to the socioeconomic, not to identity politics.

As the concept is used and understood on the socialist left, identity politics has typically meant a cultural politics of representation—diversity initiatives and so on—that exists at the expense of a materialist politics of redistribution. Put simply, it's a politics that does far too little to address issues related to class and more universalist social concerns. More accurately, we might say that identity politics is itself a form of class politics, but one that tends to express the class position of those who, on the one hand, are materially privileged enough not to have to think as much about class, and on the other, often have an interest in protecting that class position. That’s why for-profit, stridently anti-union corporations like the New York Times love identity politics: they get to exude a sheen of progressiveness by promoting it while doing nothing to challenge (or teach readers about) the material basis of so many identity-based forms of oppression. This is why the paper’s willful misrepresentation couldn’t be more predictable.

But what’s infinitely more interesting than this is the way the conversation between Piketty and Sandel involves its own misreadings of a sort related to this impoverished politics. Ultimately, what their back-and-forth really reveals is the way prominent thinkers can talk past each other when one of them fails to fully understand the implications of what we might call the recognition vs. redistribution debate.

The scholar Nancy Fraser has done more than any other to theorize the debate’s terms and it is worth recounting some of her argument here. (For anyone truly trying to understand the problem of identity politics in a critical yet non-dogmatic way, there is probably no better starting point that her work.)

For Fraser, recognition and redistribution constitute the two primary ways that different groups in society seek to redress injustice. Recognition, the primary mode of identity politics, is what groups seek when they are fighting to redress specifically cultural/symbolic forms of injustice. Redistribution, on the other hand, is what groups seek when they are fighting to address socioeconomic forms of injustice such as those prioritized by the traditional left.

It would not be wrong to say that we are in our current political conundrum largely because, over the past forty years, fights for recognition have been greatly prioritized over fights for redistribution; the working-class abandonment of the democratic party is a result of nothing if not this. Yet this absolutely does not mean that we shouldn't fight for both. The key as Fraser sees it is to realize that there are regressive and progressive versions of both fights.

Instead of simply endorsing or rejecting all of identity politics simpliciter, we should see ourselves as presented with a new intellectual and practical task: that of developing a critical theory of recognition, one which identifies and defends only those versions of the cultural politics of difference that can be coherently combined with the social politics of equality.1

In other words, if we agree that real equality and universalism should be the ultimate horizon of our politics, we should be cautious with fights for justice that end up celebrating difference in ways that are counterproductive to this egalitarian goal. We can assess this by asking: do fights for recognition and redistribution accomplish their goals by affirming or transforming the groups in question? Fights for recognition tend to overwhelmingly do the former, affirming or even performatively creating the groups demanding it. We can think here of the way certain DEI initiatives can end up reinforcing reductive, reified, or even essentialist understandings of race and gender, implying through their tokenism that these categories are more substantive than they really are, or that they have clear-cut, biologically based boundaries that account for homogeneous group experiences. We can also see how they might stigmatize the groups involved, which only helps to further impede the goal of true universalism. Yet the goal of our politics should ultimately be to constantly deconstruct and challenge (as in a properly queer politics, for example) these categories as things that are not substantive so much as cultural constructions that are deeply relational, unstable, and historically contingent, used as tools to divide and exploit us by oppressive regimes.

Of course, fights for redistribution under neoliberalism also risk affirming rather than transcending the groups involved. We can think of the way band-aid solutions like the (nonetheless needed) expansion of the welfare state affirm class boundaries by doing little to challenge the powers that keep those boundaries in place, all while stigmatizing the poor. The alternative would be more radical forms of redistribution—those that involve redistributing wealth towards collective and public forms of ownership, for example—which would make the notion of class irrelevant altogether. As Fraser writes, referencing Marx, “the task of the proletariat [...] is not simply to cut itself a better deal, but ‘to abolish itself as a class’.” The takeaway is that the left should fight for both recognition and redistribution as long as they are versions of those fights devoted to destabilizing and challenging the boundaries that impede fights for more transcendent kinds of equality and universalism.

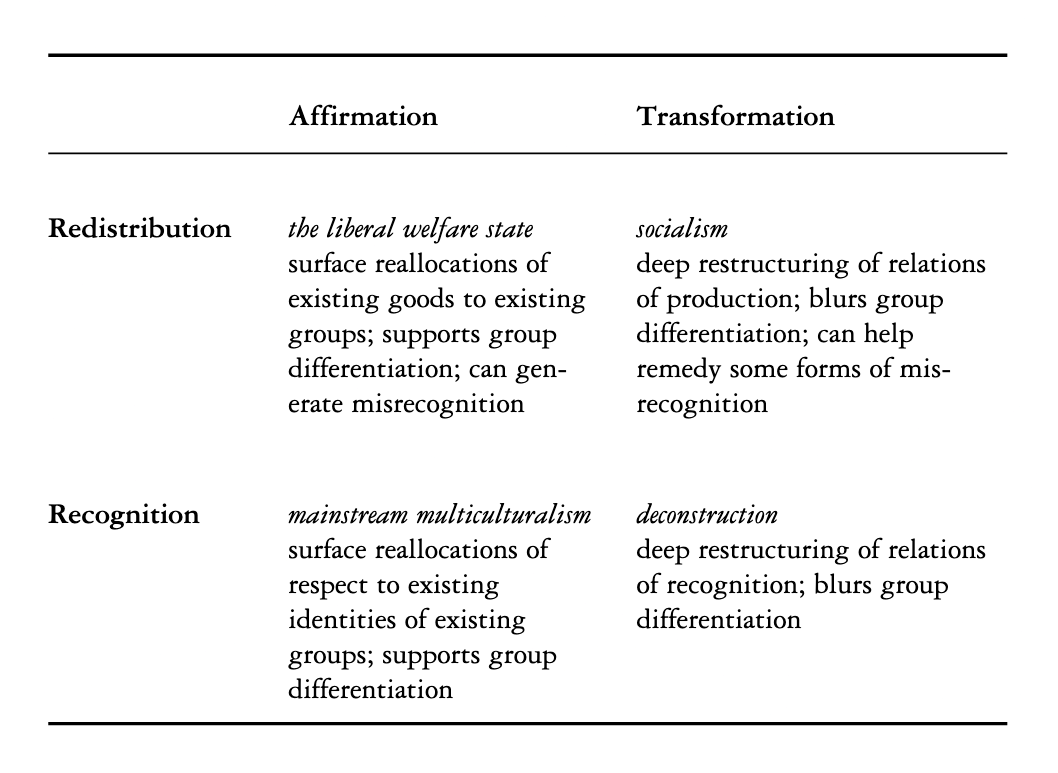

Fraser offers the following useful chart describing these differences:

To be sure, as Fraser notes, these distinctions between recognition and redistribution are largely analytical; in practice they tend to reinforce, imply, or relate dialectically to one another. To see how, we can finally turn back to the conversation. Early on, Piketty notes how the recession of class politics (a politics of redistribution) has, under neoliberalism, created an opening for a particularly nefarious politics of recognition to arise:

We’ve never been as rich as we are today. But because we’ve given up on some ambitious continuation of the egalitarian agenda of making the most powerful economic actors accountable to democratic control, making them contribute to the public goods we need to fund, you have this nativist discourse of blaming migrants or supposedly excessively open frontiers for our problems.

What he is essentially describing here is the way that a need for recognition by a discrete interest group originates in a failure of redistribution to what is presumably a much wider group (working-class people as a whole). The lack of economic and material support is the condition of possibility for the white working class (to give one example) coming to understand its hardships along those more restricted and divisive identity lines, whereas that self-understanding might have otherwise remained in the terms of the working class more generally. Put another way, redistribution can have a transformative effect not just on class but also, in this case, on race by preventing the conditions that encourage conflicts to be understood along racial lines. We might say that redistribution can discourage racialization. Yet its absence here sets the table for alternate, identity-based understandings rooted in much more divisive forms of social closure.

It would seem in this example, then, that redistribution is somehow more primary and important than recognition. Yet it’s not so simple. Would it not be more accurate to say that redistribution in this example functions as its own form of recognition? When workers are rewarded with higher pay, benefits, and long-term job security, is this not also a form of recognizing workers’ needs as an interest group? It would be hard to argue otherwise. But can we turn things around and say that recognition can also be a form of redistribution? It would seem not. Whereas the material benefits of redistribution always also have a symbolic value, symbolic benefits do not always have a material value.

Piketty’s interlocutor, Michael Sandel, seems to disagree. After offering an anecdote about being accused by a prickly Iowan of being a condescending coastal elite, he says, “my hunch is that any hope we may have of reducing economic inequality will depend on creating the conditions for greater equality of recognition, honor, dignity and respect.” Later on, he says a version of the same thing:

A progressive economic agenda is an important step in the right direction. But as Donald Trump returns to the White House, Democrats need a broader project of civic renewal. They need to affirm the dignity of work, especially for those without college degrees…

In other words, Sandel is insinuating here that recognition must precede redistribution. But how would this work? Why would some sort of vaguely conferred symbolic recognition ever need to be the precondition for material redistribution? It is an incoherent idea. The only way one could come to this conclusion, it seems, is to refuse to see economic redistribution as precisely a way of conferring “honor, dignity and respect.” After all, it is hard to think of anything that would affirm the dignity of work more than higher wages.

Amusingly, Piketty throws Sandel a bone, claiming that his position seems reasonable, but then proceeds to simply repeat what he had said above:

By continuing in the direction of the democratic socialist agenda promoted by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren [??], and hopefully by younger candidates in the future, I think the Democratic Party will be able to restore hope and a feeling of recognition to a larger part of the country than just Boston and San Francisco.

Once again, Piketty suggests, redistribution leads to recognition.

What remains to be determined, as per Fraser, is whether the redistributional measures mentioned throughout the piece (cancelling debt, raising wages, restoring jobs lost to globalization) aim to truly transform rather than merely affirm working class existence. We must say that they only do the latter. We are still largely on the terrain of liberal progressivism, not social democracy or democratic socialism. Discussions of student debt relief, for instance, foreclose more important discussions of the need for free colleges that would obviate the concept of debt altogether as well as the need for the means-tested policy that stigmatizes the working class as such. And while Piketty mentions the salience of working-class contempt for the elite, he doesn’t mention the importance of creating explicitly public amenities like public housing, healthcare, and utilities that would transfer ownership of essential goods—and thus control over working-class lives—out of the hands of the elite altogether.

Piketty also leaves out something else that might be the most important thing of all: the fact that the universalism aspired to by a truly redistributive agenda isn’t just about inching society towards more robust, pragmatically lived forms of equality; it’s also about discouraging forms of divisive race- or gender-based social closure that inhibit the cultivation of solidarity, which is the only real foundation for creating true mass-political power. Worker militancy, mass strikes, student occupations and sit-ins—that sort of thing. Another way to think about Fraser’s framework, then, is through the question of whether different forms of recognition and redistribution inhibit or encourage the creation of solidarity across different groups in the interest of creating mass political power.

What is certain is that, in the face of the current oligarchical capture of every facet of government, we need that power now more than ever. To be sure, we also desperately need the rights of trans and other people to be thoroughly recognized, to give but one timely example. Yet legal interventions that provide these forms of affirmative recognition will never be enough. What is also needed is a transformative politics that sees these categories themselves as reified tools that the ruling class uses to continually divide us from mass political solidarity and action while keeping us from seeing our common needs and common humanity. The New York Times will never promote anything but the most neutered take on this politics. Fraser’s work can help us to be better at seeing it as such.

Nancy Fraser, “From Redistrubution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a ‘Post-Socialist’ Age,” New Left Review, 212 (July/August 1995), 69.