Native Scenes from the Mall

As the Standing Rock Sioux lose another battle against the Dakota Access Pipeline, two buildings in Washington D.C. remind visitors of the permanence of the past.

The Mall in Washington D.C. can feel like a graveyard, particularly when the political mood turns south. During less turbulent times, the buildings and monuments there seem to be at least nominally animated by the ideals they represent, possessed of life in spite of their stony stillness. But during bad times, those same structures can feel dead, as though that animated spirit had abandoned them, transformed into allegories of transience. Architecture’s stillness comes to seem less like its essence and more like a tragic result. Alabaster buildings become bone.

That feeling of deadness on the Mall has always been most pronounced during the protests and marches that it perennially hosts. This might seem counterintuitive given the rivers of impassioned life that tend to define those events. But stillness is, after all, meaningless without movement. As protesters ebbed down the avenues during a recent march, it was they who gave architecture its inertia. Buildings became inept politicians, arms folded and watching from the curb. Neoclassical symmetry has never seemed so self-satisfied.

In a way, this is unfair. It is the unavoidable fate of architecture to be other than the life it shelters. Yet it often doesn’t help itself. On the Mall, monuments often seem to celebrate their own mass as much as living memory. Domes press down like dead weights on arrays of columns, as though to drive them deep into the earth. Low-slung temples of bureaucracy spread their weight over long city blocks, like iron plates covering potholes in the road. If there is beauty here, it is often heavy.

There is also the issue of isolation. The Mall’s buildings and memorials largely stand oblivious to one another, as though history itself were merely episodic, without connective tissue between people and events. It makes for a plodding geography: Here is where we celebrate George Washington. Here is where we remember Vietnam. Here is where we walk in a circle to think about World War II. In each case, the burden of meaning creation falls on solitary stone shoulders, only adding to the sense of weight.

Yet two relatively recent museums, both devoted to underrepresented peoples, are exceptions that activate and enliven this landscape in important ways. One is the Museum of African American History and Culture, whose isolation on the mall feels appropriate. As an act of wry reappropriation, it is separate and defiantly unequal, inhabiting a solitude that redoubles its symbolic function: a place to tell an alternate narrative, free from the gaze of the hegemon. In its design, which is based on the tiered headpieces of Yoruba sculpture, it is the crown of another king. In its dark color, it is a rejection of Washington’s white neoclassical officialdom. In every way, it is an architecture of repudiation. And yet that repudiation is also a gift: if before the Mall’s whiteness was invisible in its ubiquity, it now reads as a choice.

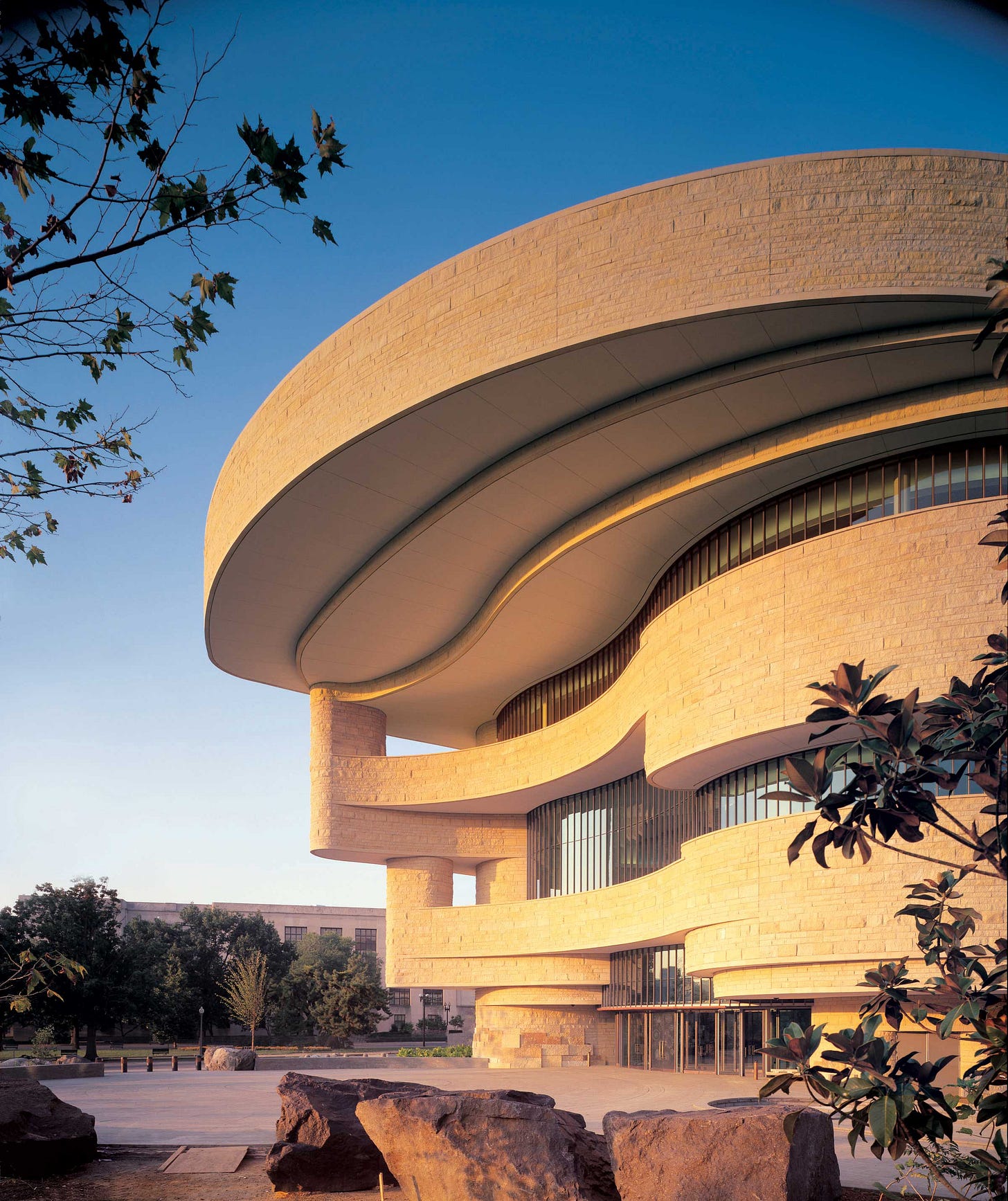

The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is something else entirely. Located on the more crowded southeast corner of the mall, the building can’t help but be read and understood in the context of its neighbors. Not that this is always easy to do. On the easternmost perimeter, tall trees, cattails, marsh marigolds, and other plants tangle into a miniature wetland that shut out the rest of the Mall while recalling what the terrain would have been like for Chesapeake Bay natives prior to European settlement. Canoes would have been made from the cypress trees, a sign tells visitors. Dolphins would have played along the waterway shores. The leafy landscaping resurrects the past while keeping out much of the present.

Or at least to a point. Directly in front of the museum, the top of a white dome breaches the trees, peering over the canopy like a watchman. The museum peers back, pointed at the dome like a needle to some questionable north. The building, of course, is the U.S. Capitol, and the tension it creates with the NMAI is palpable. It is as though two centuries of colonial power struggles had been frozen in stone.

To be sure, the NMAI is no masterpiece. The sides and rear of the building feel woefully underdesigned compared to the curvilinear dynamism of the front, which itself comes off as a bit garish. But underwhelming aesthetics do not preclude potent symbolism. Take the building's walls, for instance. Built almost entirely from rugged Kasota limestone, the museum’s earthy beige exterior dialogues uncomfortably with the white of the capitol and the rest of Washington—a tobacco-tinged tooth in an otherwise pearly mouth. It doesn’t repudiate white, as does the deep bronze of the Museum of African American History, so much as give it a certain volatility. Beige is white’s almost, not its other, a proximity that makes both colors seem nervous around one another, distrustful of one another, as though aware of how little it might take to become the other. White sullies into beige. Beige empties into white. Or whatever your metaphor might be for assimilation.

The unease between the buildings runs deep. The original capitol dome was completed in 1826, only two years after the creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which was established as part of the War Department to oversee government dealings with the natives. Its first major action would be to help engineer the Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by Andrew Jackson, which would result in the displacement of over 46,000 American Indians to lands west of the Mississippi River. On the thousand-mile Trail of Tears alone, 4,000 out of 15,000 Cherokees died.

In 1868, just two years after the redesigned capitol dome was completed, the BIA sent General Sherman to southern Wyoming to goad the Sioux into signing the second Laramie Treaty, which promised North Dakota’s Black Hills to the tribes along with the rest of the Great Sioux Reservation. It would be under the same dome that congress would pass the Agreement of 1877, which would officially break that treaty and take the Black Hills back.

Subsequent policies created at the capitol would help to reduce the native population to a third of what it had been at the beginning of the nineteenth century, to say nothing of prior colonial decimation. The BIA has since admitted to those wrongs. In a speech given to mark the agency’s 175th anniversary, then-Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin Gover apologized on its behalf: “I stand before you as the leader of an institution that in the past has committed acts so terrible that they infect, diminish, and destroy the lives of Indian people decades later, generations later,” he remarked. “Ethnic cleansing,” he had called it earlier.

The NMAI was to be the centerpiece of federal action that finally addressed all of this. The product of decades of planning by native activists and politicians, the museum was initiated over thirty years ago with the passage of the National Museum of the American Indian Act and finally opened in 2005. The standards it set for itself were daunting. In order to correct centuries of misrepresentation in museums, it would create exhibits that represented Indian culture as vibrantly alive, not as a primitive anachronism. It was to be overseen by indigenous curators rather than non-native academics. It would strive for a unified, pantribal account of Indian life. And it was to recognize that political boundaries are not cultural boundaries by giving voice to indigenous tribes across the continent.

The accomplishment, were it to be achieved, would not be small. Sioux activist Vine Deloria is said to have remarked that a museum on the National Mall would be the most significant achievement for Native Americans in a century. Tribal members treated it as such: Over 25,000 indigenous people representing more than five hundred Indian nations came to the opening on September 25, 2005. It was the largest gathering of tribes in modern history.

Yet change comes hard. That the second largest gathering of native tribes in modern history happened eleven years later but for a much less celebratory reason proved that irony would remain alive and well on the National Mall. The gathering happened far from Washington, some forty miles south of Bismarck, out on the North Dakota plains. Despite the freezing temperatures, representatives from over 250 Indian nations showed up with the intention of digging in and staying for a while. Their reason? To show solidarity with their Standing Rock Sioux brethren, who had found themselves at odds with a pipeline company intent on moving oil across the Missouri River.

The vicissitudes of the project’s fate ever since have, of course, been dizzying. President Obama shut down the pipeline only for President Trump to revive it and make it operational. In March of 2020, a court ruled that the Army Corps had failed to adequately consider the pipeline’s potential impacts on drinking water, ordering the flow of oil to be stopped while the Corps prepared a new assessment. But while the assessment is being prepared, court stays and actions by the Biden Administration have allowed the oil to flow yet again.

In the wake of these changes of fate, many will look to the NMAI’s stoic visage in relation to the capital and find some measure of native resilience. Others will see a different, much darker form of persistence. Either way, there is something about the inertial permanence of these buildings and their unsettling relationship that calls on us to never forget the turbulent history shared between them, one that, as we will see, is written in stone.

Borders

If you were to visualize the map of North and South Dakota, you might imagine two stacked rectangles with perpendicular borders, save for the eastern edge formed by the Red River. From a certain perspective, this would be a mistake. A more accurate representation would be two rectangles with several holes cut out, including one straddling the states’ central shared boundary. That hole would be the Standing Rock reservation, which begins at the Cannonball River and extends 3,572 square miles to the south.

The exact nature of Native American sovereignty is slippery, at least from a legal standpoint. American Indians are explicitly mentioned only three times in the U.S. Constitution, and only once in regard to political jurisdiction. “The Congress shall have power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian Tribes,” reads Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3. Here, the tribes aren’t separate nations, but nor are they separate states, and are to be regulated by nothing less elusive than “commerce.” It would be up to the Supreme Court to provide some clarity: tribes had an aboriginal right to land, yet they shared the title to that land with the U.S. government (Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia, 1831); or later: tribes weren’t quite foreign nations but were instead “domestic, dependant nations” whose relationship to the U.S. was that of a “ward to its guardian” (Worcester vs. Georgia, 1832).

Those ambiguities of native sovereignty persist to this day. Yet visit the website of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and you’ll read only that the relationship between tribes and the United States is “one between sovereigns, i.e., between a government and a government”—a half truth at best.

Matters are much clearer for the Sioux. Like most other indigenous groups, they refer to themselves as a nation, and not without the pride that typically attends that designation. Anyone could have sensed it during their fight against the pipeline. Despite the fact that few followers of that fight would emerge with a substantive understanding of what Standing Rock actually was or had been, and despite the fact that fewer still could speak to the exact nature of what, aside from water, was being violated by the pipeline, all could agree that, whatever Standing Rock was, it at least seemed to embody its name: an unwavering entity, determined to defend its 3,572-square-mile hole in the middle of the Dakotas from corporate encroachment.

Yet this reading also has its problems. If maps illuminate a particular spatial present, they are also acts of erasure, able to show what is only at the expense of what was. And what was in the case of Standing Rock was a vast former dominion of which the current territory is but the slightest colonial crumb.

Until 1851, Sioux territory had no boundaries apart from the unspoken borders formed by hostile tribes and hunting grounds. In 1849, when gold was discovered in California and elsewhere, this began to change. More non-natives entered Sioux hunting grounds than ever before, disturbing the distribution of the buffalo and causing conflict. In 1851, a short-lived solution was found in the Laramie Treaty, according to which the Sioux—insofar as they signed it, but not insofar as they understood it—agreed to live within roughly specified areas while allowing prospectors and others safe passage along designated roads.

When more gold was found in the early 1860s, this time at the headwaters of the Missouri River, the inundation by fortune seekers commenced. More promises were broken, more fighting broke out, and in 1868 another Laramie treaty was signed. This time, real boundaries were drawn: the Sioux would agree to live and hunt within a curtailed territory—the Great Sioux Reservation, 25 million acres that included the present-day Standing Rock territory—while once again allowing the army and others safe passage along specific roads. In exchange, the Sioux would receive both government protection and regular rations.

Benevolent though all of this might seem, it was the beginning of a federal policy that would seek to induce the very dependency the government would later use to justify its patronizing sovereignty over the Indians. As part of the treaty, it was stipulated that the Army would build an agency near the center of the reservation, which would house a government agent while serving as a distribution point for rations. As the treaty put it, the agent

shall reside among [the Sioux], and keep an office open at all times for the purpose of prompt and diligent inquiry into such matters of complaint by and against the Indians as may be presented for investigation under the provisions of their treaty stipulations, as also for the faithful discharge of other duties enjoined on him by law.

In truth, however, the agency—then known as the Grand River agency—was largely there to surveil the Sioux and facilitate containment in the event of future government intervention. In 1873, the agency was moved up the river to be nearer to Fort Yates, so that the latter could provide military support in the event of a conflagration. The building sat high up on a plateau, near bands of Cottonwood trees and a ferry landing on the Missouri. On December 22, 1874, it was renamed the Standing Rock Agency.

The Standing Rock reservation proper would come into being over the next fifteen years, which would see some of the most storied events in Plains history: General Custer’s treaty-breaking search for gold in the Sioux’s Black Hills, and the subsequent Battle of Little Bighorn, which he would lose decisively; Congress’s failed attempts to coax the Sioux into selling those hills, and its successful attempt, in 1877, at stealing them back; the murder of Crazy Horse; the murder of Spotted Tail; the murder of Sitting Bull.

All of these wounds would ultimately lead to a bigger one. In 1888, an Army commission arrived at the Standing Rock Agency to goad the beaten-down Lakota and Dakota into signing away most of what remained of their land. It succeeded. Nine million acres of Sioux territory would be ceded to white homesteading. Six smaller reservations, one of which would become the Standing Rock Reservation, were all that would remain.

From the very beginning, then, Standing Rock was a consolation. To refer to it in its earliest days was to refer not to Sioux territory proper but to the government outpost established to surveil it. It was to also refer indirectly to the surrounding forts run by the very military that, in the guise of the Army Corps, would one day allow the Dakota Access Pipeline to pass through Sioux ancestral land. When Standing Rock eventually became a reservation, the name would stand for land taken, not given. Rather than serve as an affirmation of native sovereignty, it would represent the scraps of colonial spoils—a hole in the middle of the Dakotas, yet inverted: the scantest presence, defined as much by the new absence that surrounded it as by itself.

Fittingly, the land occupied by the National Museum of the American Indian is also a consolation of sorts. The plot was the very last one remaining on the National Mall, and it was offered to native leaders only after plans for a Museum of Man, and then a combined Native and African American history museum, fell through. In a landscape devoted to national memory, the last plot available went to the first people here.

That the plot happened to be in the shadow of the U.S. Capitol is all the more appropriate, evoking a history of government-native surveillance that dates at least to the time of the Standing Rock agency, built to feign benevolence out on the North Dakota plains. As for the NMAI as a whole, we might read it as another reservation of sorts: a space of cultural efflorescence that is also one of containment, situated under the watchful gaze of white men on a hill.

The Gaze

Domes, though, are deceptive. Regardless of where one stands in relation to them, they always look as though they’re looking at the viewer, whether as the surveilled or as something else. Yet take a step away from the trees shielding the NMAI from the rest of the capitol and it becomes clear that the museum’s gaze isn’t actually reciprocated. While the museum faces the capitol, the capitol faces just past the museum, straight down the center of the Mall.

That general direction is west, which is fitting for a building that is essentially a monument to Manifest Destiny. It’s also fitting that it would look past the NMAI, since what lay under or beyond the Indians was, for the colonial imagination, always more important than the Indians themselves. The original planning mastermind of Washington D.C., Charles Pierre L’Enfant, had that colonial worldview in mind when he wrote to George Washington that the capitol “should be drawn on such a Scale as to leave room for that aggrandisement and embellishment which the increase of the wealth of the Nation will permit it to pursue at any period however remote.”

The capitol, in other words, was to be built with a future of conquest in mind. As it turned out, the original building was still inadequate and had to grow as the country grew, introjecting something of the territorial plentitude that would eventually extend all the way to the Pacific. Architects regularly added new chambers to accommodate the representatives of new states as they were added to the union. The dome would grow, too, replaced in 1866 by a grander version of the original.

Inside the rotunda, a narrative of this conquest unfolds through art. Gigantic history paintings, commissioned throughout the nineteenth century, transform the cavernous space into a site of nationalist self-fashioning. They show founding documents being signed, flags being planted, wigs being worn, wars being won. There are declarations, discoveries, and baptisms. And there is the godhead George Washington, looking down on it all from the rotunda’s apex, resting on his cloud.

There are also occasionally American Indians. And in almost every instance, and as with the NMAI and the Capitol, they look upon the conqueror without their gaze being returned.

In William Henry Powell’s Discovery of the Mississippi (1853), the explorer Hernando De Soto sits on his horse near the banks of the river, with nothing between him and the shore but a band of natives. The Indians face De Soto, cowering slightly as they offer peace. De Soto looks just past them, as do his twenty-some-odd soldiers. A small group of them raises a crucifix in the foreground.

In John Vanderlyn’s Landing of Columbus (1846), the explorer strides ashore with his entourage, sword in one hand, Spanish flag in the other. A band of naked Indians looks on timidly from behind the trees as Columbus gazes up to God. A parrot sits on a branch, no less apathetic or oblivious.

And in the frieze painted by Constatino Brumidi depicting the history of the nation in a band encircling the rotunda, another Columbus disembarks the Santa Maria as a group of Indians huddle curiously to the side. The colonizer leans slightly forward, conferring a sense of power over the tallest native who, in a parallel diagonal, leans back. They look directly at Columbus, who once again looks elsewhere.

It would have been common for indigenous people to see these images. Throughout the nineteenth century, as Indian lands were being stolen and curtailed, tribal delegations travelled to Washington with increasing frequency, often meeting with the president himself in order to try to improve the treaty terms offered to them on the plains. They cut their hair, traded buckskin for white button-down shirts, posed for pictures, and stayed in hotels. When visiting the rotunda, they would have looked at themselves looking and seen a familiar gaze that went unreturned.

On December 18, 1889, one such delegation arrived in Washington from Standing Rock. Only weeks before, the depleted Sioux had been intimidated into signing away the Great Sioux Reservation, and they were in D.C. because their rations had also been cut. Meanwhile, back at the Standing Rock agency, the government agent assigned to the reservation would look west. “The white man,” he recalled in his memoirs, was “not standing still. Nothing could deter him from going forward, and if, in the march of civilization, a people was blotted out, it would not be the first time that the same march had proved remorseless.”

Property

Walking around the museum’s trapezoidal perimeter, rimmed with native plants and wetland trappings, there’s a sense of reprieve from Washington’s rational geometries. The building itself has no right angles or straight lines, rising instead like a wind-sculpted mesa, baked in the sun. Skylights, overhangs, and curvilinear forms ease the transition from inside to outside, emphasizing native connections to nature. There is a sense that even the grid itself is shunned.

With this comes a feeling of permeability, as though something is being shared, even if it isn’t exactly clear what. Upstairs, in an exhibit on treaties, visitors are reminded of how foreign the notion of land as commodity was to most tribes. What was in the rectangle was more important than the rectangle itself. The right to land was defined by use, not title. Lived place was celebrated more than owned space.

Rectangular structures like the capitol, on the other hand, echo the grid, repeating it redundantly, as though to leave no doubts about the abstract property rights granted thereby. As a result, their message is as much about a certain way of thinking about and claiming land as it is about any particular architectural style. Owned space is celebrated more than lived place.

Though the capitol itself isn’t technically on the grid, it has long had an important relationship to it. In the late eighteenth century, when the city was still a ten-square-mile plot of bucolic farmland, L’Enfant proposed that the new district be divided into a grid whose center would be a “Congress House” high on a hill. The building would be a visual anchor, serving as both a reference point within the rationalized geography of the city and a reminder of the new federal reality to which the new city owed its existence.

But the grid and capitol would come to be linked in more symbolic and consequential ways as well. In the eyes of Thomas Jefferson, who helped design the original building, the architecture of the capitol was to convey some sense of the radical democracy the country had been founded upon. For Jefferson, that democracy went hand in hand with self-sufficient individualism as a form of independence; in the manner of the grid, with its designated plots for all, each was to have and tend to his own.

Jefferson’s obsession with bootstraps individualism was directly related to the war, which had been fought to end the dependence on, and subservience to, the British throne. What Jefferson envisioned for the new country was instead a society of unfettered individuals who ruled and supported themselves, and who expressed this self-sovereignty primarily through agriculture. Private property would be the basis of a noble individual autonomy, made more virtuous by way of the plow. “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God,” he wrote.

Yet as sensible as Jefferson’s democratic individualism might have seemed, it would also contribute to the Plains Indians’ undoing, helping to influence the next hundred years of Indian policy. It would spell particular doom for the Lakota and Dakota, who went where the buffalo went and had no use for fenced-in parcels of land. At the policy’s root was an almost evangelical faith in the ability of private property to civilize, and the related association of communal living with savagery. “The common field is the seat of barbarism; the separate farm the door to civilization,” the Sioux agent wrote in 1858. Righteous Christian reformers, together with land-lusting homesteaders, speculators, and railroad companies, agreed, lobbying tirelessly for what remained of Indian country to be further broken up into farms. In 1885, Senator Henry Dawes, echoing common misunderstandings of the nature of Indian ownership, wrote that

they have got as far as they can go, because they own their land in common [...] and under that there is no enterprise to make your home any better than that of your neighbors. There is no selfishness, which is at the bottom of civilization.

Two years later, with the passage of the Dawes Act, that “selfishness” was imposed on the plains. Indigenous lands were broken up into allotments to be used by individual Indians for farming. Boys under 18 would receive 40 acres, men over 18 would receive 60 acres, and heads of families would receive 160.

The Dawes Act hardly had the desired effect. At Standing Rock, the land left for the Sioux to farm was poor at best. And so rather than create self-sufficiency among natives, the act only increased the very dependence on the government that agriculture, in the Jeffersonian frame, was intended to prevent. The grid had come to the reservations.

Inside the museum, a placard explains the Lakota concept of mitakuye oyasin: “everything is connected, interrelated, and dependent in order to exist.” By “dependent,” this doesn’t mean “needy and reliant,” which might have been how Jefferson would have understood it. It means “dependent” as in indebted to things beyond themselves. It’s an ontological claim: we are what we are only via our connectedness to other things, which means that we should also see ourselves as indebted to those things. “To the white peoples,” writes the scholar Robert Bunge, “land is ground; to the Lakota, land is earth... the mother of all that lives, the source of life itself—a living, breathing entity—quite literally a person.”

But a plot of land cannot be a person. At the opening of the museum, Colorado senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, of the Cheyenne Nation, acknowledged as much. “[Indigenous people formed] communities inhabited by farmers and doctors, teachers and craftsmen, housewives and soldiers, priests and astronomers, who with all their collective wisdom could not have known that earth mother would someday be called real estate.”

Water

A river can be a boundary, of the grid or otherwise. But a river can also imply a certain boundlessness in the movement it manifests and the sustenance it offers forth. At the river, there is edge, limit, precipice. In the river, there is flux, renewal, change.

Political boundaries offer no such sustenance. They do not contain their opposite, as does the river, moving and flowing despite themselves. They are lines in the abstract geometric sense—in theory, infinitely thin and thus incapable of offering anything but their own juridical nature. They are lines delineating space, not place.

When the eastern boundary of the Great Sioux Reservation was set at the Missouri River in 1868, it was not because the Sioux had wanted it that way. But it was at least a political boundary that coincided with a natural one—a boundary that could also be a bounty, both of sustenance and of spirit. Water for the Sioux was essential not only for its capacity to sustain life on the arid plains, but also as a spiritual substance to which they, in the spirit of Mitakuye Oyasin, saw themselves as connected and indebted. If Sioux lands were to be bounded on the East by the Missouri River, they could at least say that their territorial and spiritual origins were one.

When the Great Sioux Reservation was broken up in 1889, the river became the easternmost border of smaller reservations, including Standing Rock. Many know this today because, from August 2016 to January 2017, the river was in the news as the main entity threatened by the pipeline—one lineal bounty encroached upon by another. What was lost on most followers of the story was that the river was, like the Standing Rock reservation itself, already a consolation prize of sorts, given to the Sioux in the late nineteenth century as so much else was being taken away. Yet what was further lost was the fact that, almost sixty years prior to the DAPL fight, the Missouri River had itself been made to deprive the Sioux of their rightful property, and by the same entity that would later grant the easements allowing the pipeline to violate the river.

In 1959, the Army Corps of Engineers seized control of the Missouri River shoreline to begin construction on the Oahe Dam, just north of Pierre, South Dakota. It did so mere months after the Standing Rock Sioux had ratified their 1959 constitution, which spoke, in its very first sentence, of the spiritual importance of water before reaffirming that the eastern border of the reservation was the middle of the river.

Yet that border itself would, in a sense, be made to encroach on Sioux land. When the Oahe Dam was completed, it would flood 56,000 acres of Standing Rock territory. 90% of the reservation’s timbered area was lost, as were wildlife resources, gardens and wild fruit trees, and the area’s most valuable rangeland. 900 families had to be relocated. No public works project in the country’s history had destroyed more land. According to Deloria Jr., it was the single most destructive act ever perpetrated on any tribe by the U.S.

The water that ended up flooding the Standing Rock Reservation would ultimately become Lake Oahe, which was ironic given that, in the Dakota language, oahe means “a place to stand.” Yet only a figurative uprightness was intended: the lake was named after the Oahe Mission, a Christian boarding school established in 1874 to bring the Sioux to Jesus.

During the fight over DAPL, then, it was as much Lake Oahe as the Missouri River proper that the Standing Rock Sioux were fighting to protect. Yet because the shoreline was still controlled by the Army, the Sioux had to fight insult from a position of injury, forced to ask permission from the government to protest on their own ancestral land. The government acquiesced, but not without offering a reminder and some advice: “Among our many diverse missions is managing and conserving our natural resources,” a spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers proclaimed. “I want to encourage [the protesters] who are using the permitted area to be good stewards and help us to protect these valuable resources.” Mere months later, the same Army Corps would allow 500,000 barrels of oil per day to begin flowing beneath the river.

There would be one more occasion for the Missouri River to be turned against the Sioux. On November 20, 2016, police would use water cannons against the water protectors to push back their advance, soaking them in the middle of the sub-zero night. Memories of the Lake Oahe flooding would inhere in the drenching: a wellspring once again weaponized even as it continued to stand for life.

In the 1990s, when the NMAI was being planned, a committee traveled around the continent soliciting opinions from indigenous leaders on the larger themes such a museum should cover and convey. One of the most common answers was the indigenous respect for water. Today, that respect manifests itself in the waterfall that spills over rocks on the museum’s north side, and also in the reconstructed estuary wetlands that occlude most of the capitol from view.

Yet well over a century before the museum was built, the fate of Native Americans in relation to water was already written in the rotunda of the capitol dome, in those paintings in which the native gaze goes unreturned. In almost every canvas, water is a central character, yet one that serves not as a bounty but as a boundary that has either just been breached or is about to be. Explorers stand on shorelines, ready to plant their flags. The water itself is of no interest to them, except to the extent that it and those dependent on it are in the way of getting to the other side.

Bones

We go to museums to learn about things like colonialism and the closing of the frontier. We trust that history taught through objects means objectivity, and that the provenance of the objects themselves is beyond reproach. Yet what we forget is that museums, too, have benefited from breached boundaries and even encouraged them in turn. Historically, it is to the museums that have gone the spoils, and few institutions have done more to consolidate the colonial imagination than they.

For decades at museums across the country, it was customary to find Native Americans and their artifacts depicted or displayed in the vicinity of dinosaurs, implying that indigenous peoples were not only less than human but also extinct. It was equally common to find them arrayed in a continuum ranging from the savage to the civilized, reinforcing racist ideology and helping to justify the national project of pushing ever further west; barbarism, as it were, had to make way for “progress.” Museums made Native Americans seem like a bygone curiosity, and all under the guise of public enlightenment.

There were also the bones. In 1839, in support of a government effort to justify colonial expansion through science, the anthropologist Samuel Morton wrote an article suggesting that American Indian crania were on average five cubic inches smaller than “Caucasian” crania, supposedly proving differences in intelligence. Similar studies followed, resulting in a craze for Indian skulls, which could be sold to the government for cash. Graves were robbed and burial sites pilfered, with the spoils going to places like the Army Medical Museum at the behest of no less than the surgeon general himself. As many as two thousand of those skulls, together with countless other Indian remains, would eventually find their way to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, of which NMAI is a part.

For years, Native American groups had requested that the Smithsonian return these and other human remains, funerary objects, and sacred items it had long held in its collections. Their reasons had as much to do with propriety as with property: for the Lakota, the spirit was thought to survive after death, and were it not properly cared for, it would begin to wander. Thirty-one years ago, in 1989, the tribes got their wish. With the passage of the National Museum of the American Indian Act, Congress initiated the process of repatriating thousands of objects to the tribes while also promising them a place to put them—the NMAI—on the National Mall.

This was important. Objects are not just the things that museums use to teach. Accumulated largely through dispossession, they have traditionally been the source of museums’ cultural power. Where the objects have gone, so too has the authority to talk about them and their history. With its objects returned, the native curators at NMAI could now be the one to control those stories.

There is poetic justice here. If the NMAI emerged in conjunction with a return of the native dead, then we could say that Standing Rock and other plains reservations emerged in conjunction with their relinquishment of those dead. For much of their history, the Lakota, Yanktonais, and other tribes buried their own on the plains. When, in 1889, the government dissolved the Great Sioux Reservation, creating the six smaller reservations we know today, any of the Sioux who’d been buried outside of reservation lines would have been stranded. The deceased were once again left for dead.

There was a brief moment on the reservation when none of this mattered. By the 1890s, word had spread among the Sioux of a new religion, the Ghost Dance, whose guiding belief was that the Indian dead would one day come back to inhabit the earth. Among them would be a Jesus-like messiah, who, having been crucified by the whites, would reappear for the Indians alone.

Take this message to my red children and tell it to them as I say it. I have neglected the Indians for many moons, but I will make them my people now if they obey me in this message. The earth is getting old, and I will make it new for my chosen people, the Indians, who are to inhabit it, and among them will be all those of their ancestors who have died, their fathers, mothers, brothers, cousins and wives…

The messianism would be short lived: any momentum the Ghost Dance had would be snuffed out on December 29, 1890, at the massacre at Wounded Knee.

But history would continue to find other ways to keep the Sioux from reinhabiting the Earth. On September 3, 2016, to clear the way for DAPL, workers from Energy Transfer Partners bulldozed a plot of land thought to contain a number of the Sioux dead, along with prayer rings, cairns, and other sacred artifacts. It was done on a holiday weekend, just a day after tribal experts filed papers identifying the archeological importance of the site. The government had yet to intervene.

Epilogue

It is tempting to believe that when we walk the National Mall, we move through some sort of extruded manifestation of the national consciousness. In this fantasy, the symbolic seat of that consciousness is the capitol, resting at the eastern end like a head. Nothing of the nation’s past is, in this scenario, forgotten. History hangs before the conscience of congress like a momento mori, influencing its every step, commanding at least part of its gaze.

But a more fitting metaphor for the mall—at least during dark times—would be more impersonal, more bureaucratic. In this interpretation, the Mall is, from the perspective of the capitol, a kind of administered scene governed by the division of labor. Here, remembering is outsourced—someone else’s problem to deal with. The individual monuments and museums aren’t so much chapters of the national past as buildings made by the capitol to remember history so that it, and maybe anyone else, doesn’t have to.

The native activist Suzan Shown Harjo had hoped that the NMAI’s relationship to the capitol would be different. In helping to plan the building, she remembered envisioning a “cultural center that would stand in the face of Congress so that policymakers in the U.S. Capitol would have to look us in the eyes when they made decisions about our lives.” But that was never to be. The capitol has long been a building that only looked as though it was looking, and foundational perspectives—be they westward or colonial—have proven tough to reorient.

If it is difficult to imagine things otherwise, it is because the persistence of our buildings can’t help but evoke the permanence of the past. It has proven to be that way even after modifications. On Veterans Day, in November of 2022, a new addition was added to the museum grounds—the National Native American Veterans Memorial, built to honor Native Americans who fought alongside U.S. troops in military combat. To construct the monument, space had to be made amid the trees, many of which had helped to do the work of blocking the capitol from view while recreating the Chesapeake Bay environs as they were before contact with the colonizers, to say nothing of the cavalry. While the new monument offered welcomed recognition of native service, native land had, in a sense, been ceded again: an area originally intended to celebrate the Indians’ prelapsarian separateness gave ground to a monument that celebrated their assimilation.

Traditionally, this is what the capitol has wanted: to see Native Americans not as U.S. citizens with an asterisk, with one foot in U.S. sovereignty and the other in a separate nationhood, but as fully folded into the national project. It has preferred that the monuments and memorials on the National Mall be, like it, marble and white. Yet the NMAI’s gift to the National Mall is that, whatever its architectural merits or failings, it will forever be a part that cannot resolve into the national whole without leaving a remainder, complicating the dialectics of this symbolically charged space.

But why a gift exactly? Because it is a refusal of ideological closure and forgetting at a time when these things seem to be as tempting as ever. In South Dakota, by the end of 2020, Native Americans had accounted for 14% of U.S. COVID-19 deaths while representing just 1% of the population. At Standing Rock, enough tribal elders died from the virus that the survival of the Lakota language was and continues to be threatened. And this is to say nothing of the violence—symbolic and otherwise—of the pipeline. The possibility still remains, in other words, that an entire people could be “blotted out.” But that remains, as it were, to be seen.