"Look Away!"

On the class ideology of the song "Dixie"

To one degree or another, ideology always involves distraction. Ensure that one narrative, psychological framework, or form of common sense is so dominant in explaining the order of things that it keeps people from looking for alternatives. In terms of the American working class’s understanding of its material struggles, those distractions have often come in the form of black and brown people turned into scapegoats by opportunistic politicians. This is in part thanks to specifically American phenomena like Jim Crow, whose legacy of perpetuating slavery’s racialized division of the workforce remains very much with us. In the framing of Trump 2.0, for instance, immigrants—not policy or modes of production—are to blame for the material issues faced by the majority of working-class Americans, seen as a parasitic drain on scarce resources. The consequence of this is a class divided. Rather than fight together against capital as a single, and hence more powerful, racially and ethnically diverse class, workers have often been coaxed into fighting against one another as status groups within the class in competition for what is perceived to be a limited pool of goods—wages, benefits, and housing, among others. All of this distracts workers, the thinking goes, from considering how the pool itself might be enlarged by more solidaristic efforts that take on capital ownership in general and its normalized hoarding of profits.

If culture has at times played an indispensable role in stoking these divisions via distraction, then few of its offerings have helped more in this ideological work than the song “Dixie.” While we tend to associate the song today with the dubious racial, not class, politics of the Confederacy, in truth the two were always inextricably intertwined. Written on the eve of the Civil War, the song’s earliest versions aided in the cultural work of leveraging racial hierarchy to distract from the emerging class consciousness of its proletarian fans. As the song moved from North to South, it would bury its racial and class references to become something even more deeply ideological: a nostalgic portrait of a leisurely land of plenty that made no mention of the work—enslaved or otherwise—that had gone into producing it.

Accounts of “Dixie’s” origins conflict, yet research suggests that the melody likely came from the playing of a family of black musicians in Ohio, which was adapted in the 1850s by Dan Emmett, a white man, for the minstrel show. By that time, the minstrel show had become hugely popular in the north, attracting vast working-class audiences eager to see acts like Christie’s Minstrels and Bryant’s Minstrels black their faces with burnt cork, strum banjos, and lampoon the degraded races by way of their garish brand of vaudevillian song and dance. Members of the learned classes were no less immune to its appeal; as a testament to the complex politics of the time, Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, and Mark Twain could also be counted as fans.

The impact of these shows on nineteenth-century popular culture is tough to overstate. This is in part because of the vast repertoire of widely known songs like “Dixie” that the shows produced. But it was also because of the way the shows helped to mediate and consolidate mid-century notions of class. It was at the minstrel show that working-class audiences could begin to understand themselves as such, positioned in opposition to the genteel elites that had begun gathering at their own exclusive theaters elsewhere about town. If that emerging class consciousness was a source of anxiety for the audience, then an important function of the minstrel show was to assuage it, deflecting attention away from class inferiority by foregrounding white racial superiority. Black characters were routinely tricked, mocked, and abused, allowing white audiences to look down on a racialized other even as their class insecurities were in many ways one and the same.

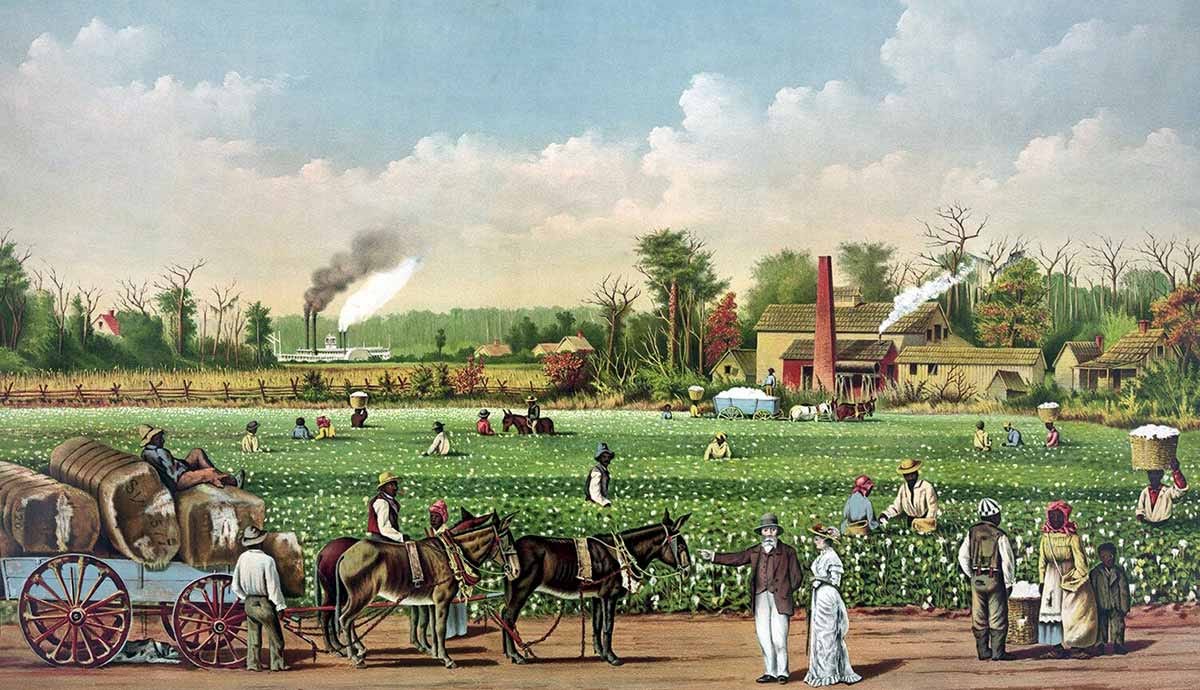

In the late 1850s, as civil war became more and more inevitable, the racism in the minstrel show came to have a double function. The prevailing political opinion in the north, best described as support for Jacksonian democracy, held that the best way to preserve the union was to leave slavery unchallenged. This was in part due to the pro-slavery position of the southern democrats, whose influence had forced the national party to adopt a similar stance. Despite the fact that much of the minstrel show’s working-class audience would go on to fight for the Union, the show itself largely espoused this pro-slavery Jacksonian position. Of the many ways it did this, downplaying the brutalities suffered by the enslaved was one of the most common. In skit after skit, masters were depicted as benevolent and plantation life as bucolic, in effect helping to make the pro-slavery position more palatable to whites eager to avoid war.

“Dixie” entered the picture precisely here. In its original form, the song would have been performed by a white man in blackface, who would have sung the lyrics in dialect:

I wish I was in land ob cotton,

Old times dar am not forgotten

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

The presence of dialect was consequential. It meant that, rather than expressing the nostalgia of a southern white protagonist yearning for home, as does the version of “Dixie” we know today, earlier versions of the song would have expressed the nostalgia of a free northern black person yearning to return to conditions of slavery. The song thus served as a vehicle for one of minstrelsy’s most enduring yet malicious tropes: the former slave unable to cope with his or her freedom, pining for life under a benevolent master back down on the plantation. The original “Dixie,” then, hardly repressed racism; it mocked blacks while downplaying their suffering, helping to make a slippery political position easier for northern audiences to digest.

This would all change once the song made it to the South. It did so quickly, arriving in New Orleans before Emmett’s version had even been copyrighted for the New York stage. Once there, the first thing to go was the dialect, which was dropped after members of the southern literati denounced it as lowly. The first verse would eventually become

I wish I was in the land of cotton,

Old times there are not forgotten,

Look away! Look away! Look away, Dixie Land.

The ramifications of this were profound. Dropping the dialect had the effect of removing any racial and class signifiers from the song, clearing the way for white southerners themselves to assume the place of the song’s protagonists. The “land of cotton” could then become the central metaphor for the revised fantasy of the song: a bountiful domain of whiteness, free from black bodies of any sort.

Yet this fantasy extended well beyond race. By calling the dialect “lowly,” the southern literati were conflating race with class in a way that was common throughout the South. The Alabama constitution, written to accompany secession, put it plainly: “Let there be but two classes of persons here—the white and the black. Let the distinction of color only be distinction of class.” As such, by purging the dialect, the southern “Dixie” modified the way that class was repressed from the song. If the northern versions concealed the brutal working conditions of those who labored without compensation, the southern versions hid the laborers themselves, further burying the structural conditions that underwrote the planter class’s standards of living. The song could now express the implicit perspective not merely of whites but of a different class of whites, those who had to do the least laboring of all: the capitalist plantation owners themselves.

As it moved from north to south, then, “Dixie” became an even more potent instrument of class ideology. For working class whites to sing it was now hugely ironic, given that, while they weren’t enslaved in the sense that blacks were, they lived a life of labor that contrasted markedly from the plentiful life described in the first verse of the song. But this was all the more fitting. The Confederacy had been ideologically based in manipulating poor subsistence and yeoman farmers into overlooking their own class realities so that they would fight in the war on racial grounds, which, in Jefferson Davis’s view, made issues of economic class obsolete. “[Slavery],” he wrote, “raises white men to the same general level [...] it dignifies and exalts every white man by the presence of a lower race.”

Davis’s statement was as revealing as it was manipulative. Echoing the logic of the minstrel show, it implied that whites—and white men in particular—were dignified only to the extent that they robbed that dignity from others, that whiteness and white masculinity needed blackness to exist as such. It was an admission of dependency masked as a celebration of hierarchical difference. But it was just as much a confession of the deeper material truths that underwrote this white masculinity along with the more general way of life that a slaveholder like Davis surely enjoyed: a capitalist order that itself required the subjugation of others—rationalized by deeming blacks less than human, consigned to nature and not culture—to exist at all. Gender, class, and race couldn’t have been more inextricably entwined.

The end of the war made all of these forms of dependence painfully apparent. When the South lost, there was no bigger wound than the one inflicted on collective southern manhood. Defeat was humiliating to men, who had failed to prevent their way of life from being upended by outsiders. Losing the war was only part of the issue: there was also the fact the patriarchal order at home had been upended. The more privileged of the fighting men returned to wives who, in the absence of their husbands, had been forced to assume the role of both master of the slaves and provider for the household, turning normative southern gender roles on their heads. Never before had the degree to which those roles depended on the free labor of slavery, and thus on a capitalist order that required it, been so clear. In essence, men had ironically depended on the slaves to be masters. Once the slaves were freed, so was the ability to be a certain type of man.

It’s easy to see how “Dixie,” a nostalgic song about a bygone south, might have figured in here. If before the war, the song’s southern versions had been a call to arms to defend the southern way of life, the song now seemed to be a melancholic reminder that that life was now lost. For the first time in the south, the nostalgia and longing of the song’s first verse actually made sense: the south, as it was once known, was now truly “away,” as the song said it was. And so was the model of patriarchy, underwritten by a particularly vicious brand of expropriative capitalism, that had sustained it.

If “Dixie” now helped to mourn the loss of these things, it could also serve as a call to preserve what of the Old South still remained, or at least what of it southerners fantasized still remained. In the wake of the Confederate defeat, men created organizations such as the Klu Klux Klan in which the south—and white supremacy and southern patriarchy—could be continued by other means. And they attempted to redeem the patriarchy itself by treating the symbolic figures in which they saw themselves—figures like Robert E. Lee—not as fallen and emasculated but as the very embodiments of brave and honorific manhood.

“Dixie” was essential in promoting these fantasies. Yet it would also help to steer them in a different direction. The repression of class references from the song had already helped it to serve the ideological purposes of the Confederacy during the war. Yet it would be the song’s repression of both class and race that would eventually help it to serve the South in a new way. The Lost Cause had emerged as a way for southerners to nurse their wounded pride by reclaiming ownership and definition of the South, yet in a way that conveniently left questions of slavery and chattel capitalism unmentioned. In an act of face-saving, it would insist that the Civil War had been fought to preserve southern heritage in general, not the malicious system of human bondage that made it possible. Yet in doing so, defenders of the South—of Dixie—would only echo the ideology of capitalism itself: a deeply ingrained way of life made to seem free and fair only by disavowing the expropriated labor that makes it possible. If the denizens of Dixie have “looked away” from anything over time, it is this.